Have you ever found yourself endlessly scrolling through your phone, skipping workouts, or reaching for a sugary snack after a stressful day — even though you swore you’d do better tomorrow? You’re not alone. Habits, both good and bad, shape a massive portion of our daily lives. According to research, up to 40% of our daily actions are driven by habit rather than conscious decision-making (Neal et al., 2006). So if we want to make meaningful, long-lasting change, we need to learn how to change our habits.

In this article, we’ll explore proven strategies for breaking bad habits and building good ones — using ideas grounded in behavioural science and popularised by James Clear in his bestselling book Atomic Habits. We’ll also provide a simple framework you can start using today to transform your behaviour and build the kind of life you truly want.

Understanding How Habits Work

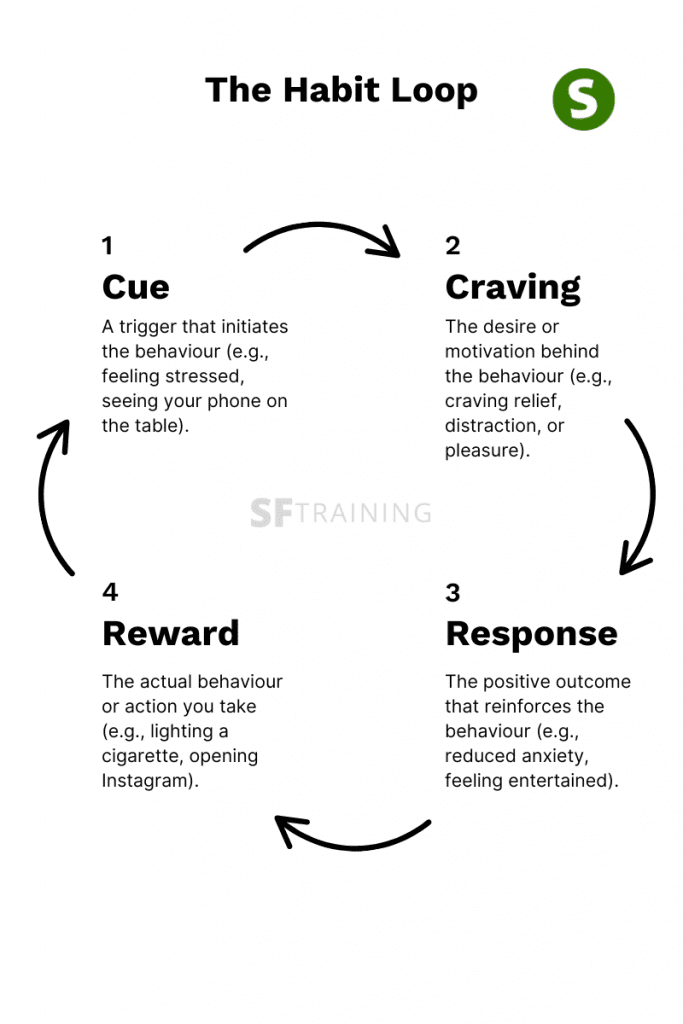

To change a habit, it helps to first understand how habits form. James Clear breaks down the habit loop into four key stages:

- Cue – A trigger that initiates the behaviour (e.g., feeling stressed, seeing your phone on the table).

- Craving – The desire or motivation behind the behaviour (e.g., craving relief, distraction, or pleasure).

- Response – The actual behaviour or action you take (e.g., lighting a cigarette, opening Instagram).

- Reward – The positive outcome that reinforces the behaviour (e.g., reduced anxiety, feeling entertained).

This cycle is powerful. The more often you repeat the loop, the more automatic it becomes. Eventually, the behaviour is so ingrained that you hardly think about it.

To break a bad habit, you need to disrupt this cycle. To build a good one, you need to establish a new one that feels rewarding and easy to repeat.

The Habit Change Framework: 4 Laws of Behaviour Change

James Clear introduces a simple but powerful framework for building better habits, based on four laws:

- Make it obvious (cue)

- Make it attractive (craving)

- Make it easy (response)

- Make it satisfying (reward)

To break bad habits, you reverse the process:

- Make it invisible (remove the cue)

- Make it unattractive (reduce craving)

- Make it difficult (increase friction)

- Make it unsatisfying (add negative consequences)

Let’s go through each part of this framework with practical advice and scientific backing.

1. Make It Invisible (or Obvious)

Changing habits starts with your environment. If you’re constantly exposed to cues that trigger your bad habit, it’s almost impossible to resist.

For example, if you want to cut down on snacking, don’t leave crisps or biscuits on the kitchen counter. Remove the visual cue. Similarly, if you’re trying to build a reading habit, keep a book visible on your bedside table or next to the kettle.

A 2012 study published in Health Education & Behavior found that participants who placed fruit in visible bowls ate more of it than those who kept fruit out of sight (Wansink et al., 2012).

Tip: Redesign your space to support your goals. Remove triggers for bad habits and add visible cues for good ones.

2. Make It Unattractive (or Attractive)

Bad habits often serve an emotional need. You smoke to relax, scroll to escape, or snack when bored. If you want to stop a bad habit, you must make it feel less appealing — and find healthier ways to meet the same need.

James Clear suggests using temptation bundling to make good habits more attractive. This means pairing something you want to do with something you need to do. For example, only listen to your favourite podcast while walking or doing housework.

Also, change your internal narrative. Instead of saying “I can’t eat that,” say “I don’t eat that.” One study found that this subtle language shift significantly increases willpower and self-control (Patrick & Hagtvedt, 2012).

Tip: Replace bad habits with healthy alternatives that offer similar emotional rewards. Reframe your self-talk to strengthen your identity.

3. Make It Difficult (or Easy)

The easier a behaviour is, the more likely you are to do it. That’s why it’s so easy to check your phone — it takes just one second. But if you have to walk across the room to get it, you’re less likely to bother.

This is where the concept of friction comes in. By adding friction to bad habits, you make them harder to perform. Conversely, by reducing friction for good habits, you make them easier to repeat.

For example:

- Log out of social media apps to add an extra step.

- Keep junk food out of the house.

- Lay out your gym clothes the night before.

A 2006 study in American Journal of Preventive Medicine showed that people who prepared their workout clothes ahead of time were significantly more likely to exercise in the morning (Sallis et al., 2006).

Tip: Add steps and barriers to your bad habits. Remove as many steps as possible for your good ones.

4. Make It Unsatisfying (or Satisfying)

The final and perhaps most important part of habit change is feedback. Our brains are wired to repeat behaviours that are rewarding. That’s why bad habits stick – they provide immediate gratification, even if they’re harmful long term.

To build good habits, you need to make the rewards visible and immediate. For example:

- Track your progress on a calendar.

- Celebrate small wins.

- Use a habit tracker app.

Conversely, make bad habits feel less rewarding. You could add accountability by telling a friend your goal. Or set up a financial consequence – if you don’t stick to your plan, you donate money to a cause you don’t support.

According to behaviour science, immediate consequences have a stronger impact on behaviour than delayed ones. So, focus on creating immediate positives for good habits and immediate negatives for bad ones (Skinner, 1953).

Tip: Reward good behaviour right away. Make bad behaviour feel unsatisfying.

Habit Stacking: The Secret Weapon

One of the most effective strategies from Atomic Habits is habit stacking. This involves linking a new habit to an existing one, using the format:

“After [current habit], I will [new habit].”

For example:

- After I brush my teeth, I will floss.

- After I put on the kettle, I will do five squats.

This technique leverages the existing neural pathways of established habits to build new ones more easily. It’s powerful because it removes decision-making and anchors your new behaviour to something already familiar.

Identity-Based Habits: The Key to Long-Term Change

Many people try to change habits by focusing on outcomes (e.g., lose weight, save money). But Clear argues that long-term success comes from focusing on identity — deciding the type of person you want to become.

Rather than “I want to lose weight,” think “I’m the kind of person who works out daily.”

When you tie your habits to your identity, your behaviour begins to reinforce your sense of self. Every workout, healthy meal, or early night becomes a vote for the kind of person you want to be.

This concept aligns with the theory of self-perception in psychology — that we develop our identities by observing our own behaviour (Bem, 1972).

Tip: Focus on who you want to become, not just what you want to achieve. Build habits that align with that identity.

Common Pitfalls (And How to Avoid Them)

Even with the best intentions, change is hard. Here are a few common mistakes and how to avoid them:

- Doing too much at once: Start small. Build momentum before scaling up.

- Being too vague: “Exercise more” is too general. “Do 10 push-ups after breakfast” is specific.

- Missing one day and quitting: You’re human. Missing once is fine. Just don’t miss twice.

Remember: success isn’t about perfection. It’s about consistency. Build systems, not just goals.

How to Break Bad Habits and Build Good Ones: A Practical Guide Inspired by Atomic Habits

Habits are the foundation of success in every area of life – health, relationships, work, and personal growth. But breaking bad habits and building new ones isn’t about willpower or motivation. It’s about creating an environment that supports change and following a proven framework.

By using the strategies from Atomic Habits – making cues obvious, cravings attractive, responses easy, and rewards satisfying – you can design habits that work for you, not against you.

Start small. Stay consistent. Focus on identity. And remember: every action you take is a vote for the kind of person you want to become.

References

- Neal, D. T., Wood, W., & Quinn, J. M. (2006). “Habits—A Repeat Performance.” Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15(4), 198–202.

- Wansink, B., et al. (2012). “Slim by Design: Serving Healthy Foods First in Buffet Lines Improves Overall Meal Selection.” Health Education & Behavior.

- Patrick, V. M., & Hagtvedt, H. (2012). “I Don’t” versus “I Can’t”: When Empowered Refusal Motivates Goal-Directed Behavior.” Journal of Consumer Research.

- Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and Human Behavior.

- Bem, D. J. (1972). “Self-Perception Theory.” Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 6, 1–62.